Informations diverses - Diverse information

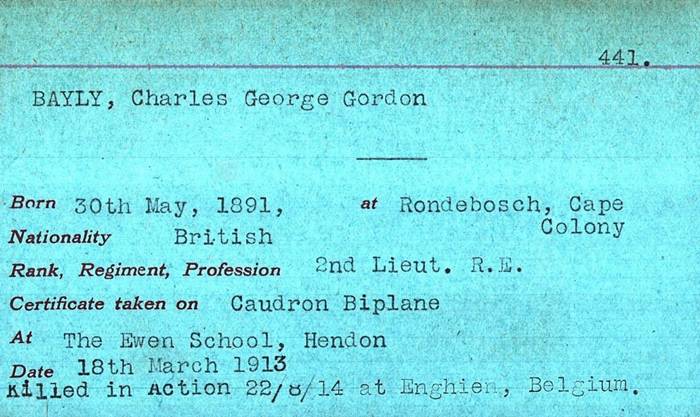

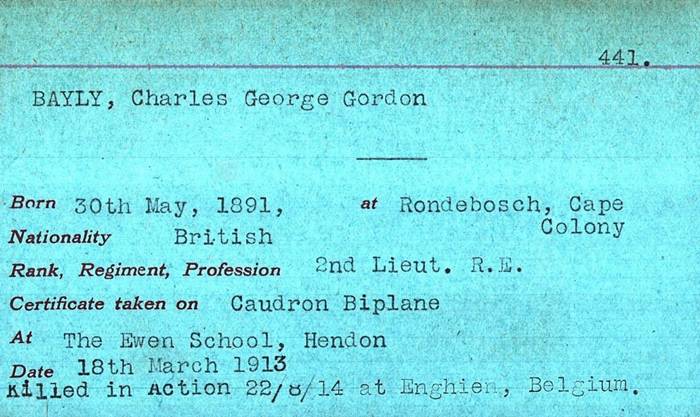

Licence de pilote de Charles Bayly, acquise sur biplan Caudron, le 18/03/1913

Pilot's license of Charles Bayly, acquired on biplane Caudron, on 18/03/1913

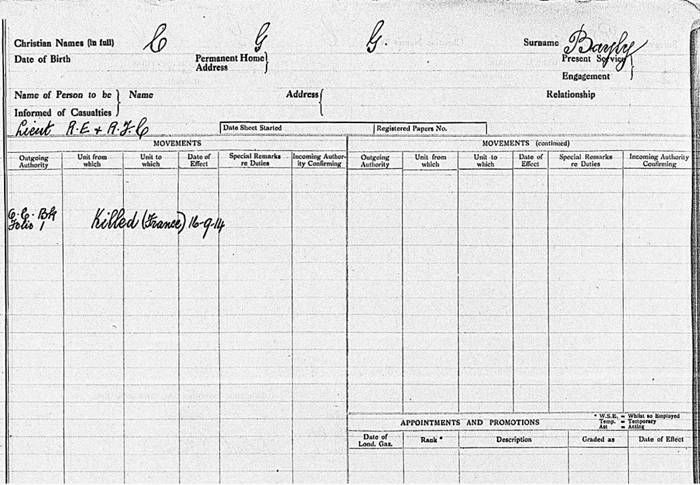

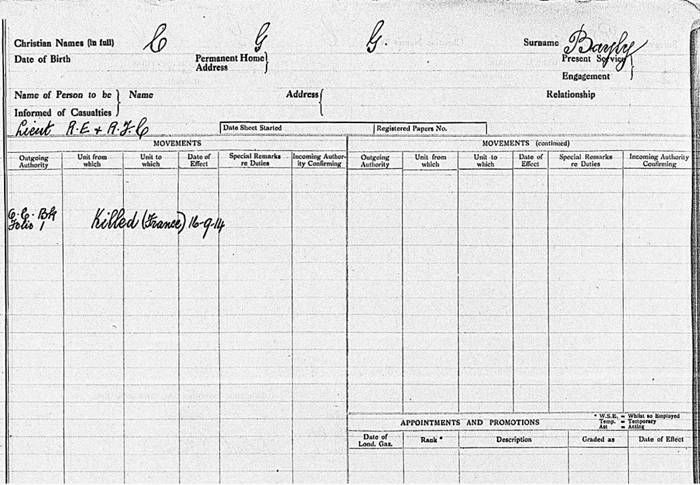

Notification du décès en mission de Charles - Announcement Charles's death in action

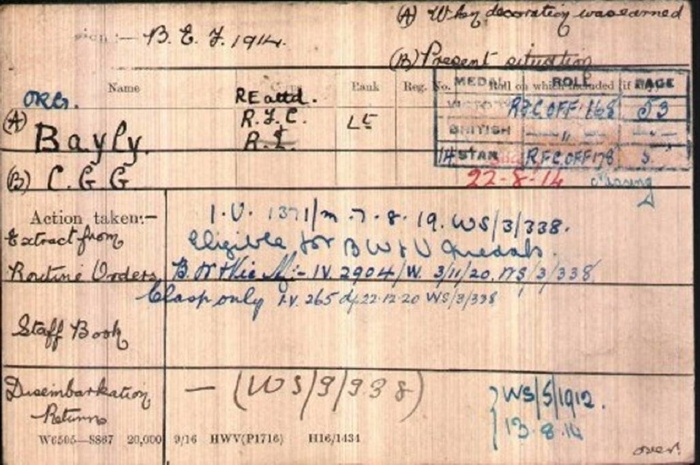

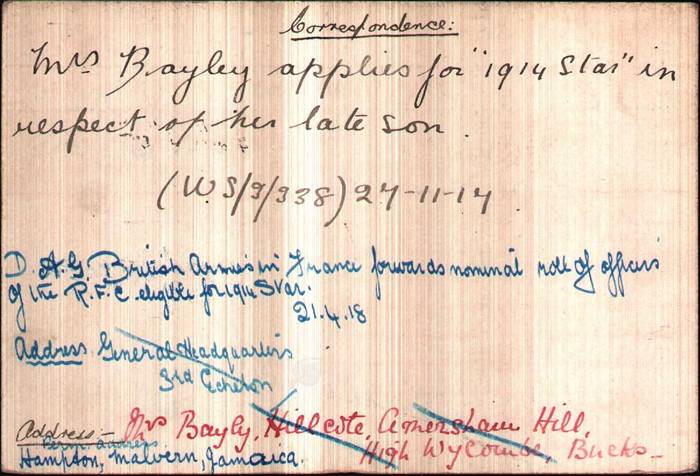

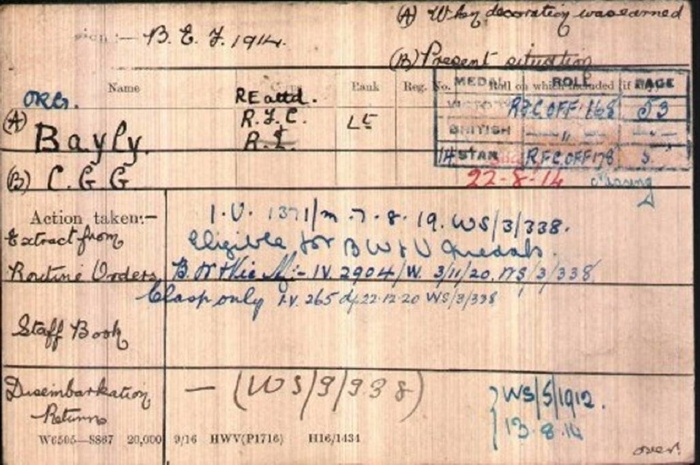

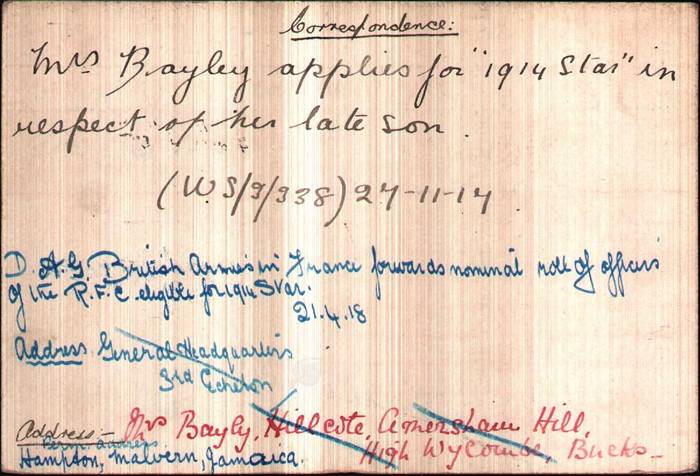

Indication d'éligibilité de Charles pour une décoration - Indication of eligibility of Charles for "Star 1914" medal

Lt Charles George Gordon Bayly RFC: aboard the first British aeroplane to be shot down

Royal Engineer Lieutenant Charles George Gordon Bayly, great-nephew of Gordon of Khartoum, after whom he was named, trained as a pilot in 1912 and earned Aero Club Certificate 441. In May 1914, as the storm clouds of war gathered far beyond the Wiltshire horizon, he polished his aviation skills at the Central Flying School (CFS), Upavon and talked of telegraphy and strut-wire tension in the mock Tudor-style officers' mess.

That summer the Archduke stopped his fateful bullet in Sarajevo, and the Central Powers careered into war. On 4 August Britain declared war on Germany. As the Schlieffen plan swung into action, Lieutenant Bayly joined 5 Squadron Royal Flying Corps. He had only a week to prepare for his flight to France on 12 August. Young pilots were eager to prove themselves, although their precise wartime role was unclear; most important was to get into the fight before it was finished.

Bayly flew his machine from Dover to Amiens in France, and then onwards to Maubeuge, a key fortified town and railway centre near the Belgian border, hard by Marlborough's old battlefield of Malplaquet. This was no sudden choice: eight years before, British and French military staff had agreed Maubeuge as assembly point for an Expeditionary Force of 100,000 British troops to combat any invasion of neutral Belgium.

With half its regular battalions scattered throughout the Empire, Britain could not make good its promise in August 1914, but the RFC showed willing, despite scepticism on high. Cavalry officer Douglas Haig told a meeting: 'I hope none of you gentlemen is so foolish as to think that aeroplanes will be able to be usefully employed for reconnaissance in the air'. By 1915, when General Trenchard took command, they were playing a vital part, but the average life expectancy of a new RFC pilot arriving in France was just seventeen days. For the first and last time in his life, keen sportsman Charles Bayly would post a score well below average.

The RFC swiftly mobilised some 860 officers and men at Maubeuge with all twenty of its remaining planes – two had crashed en route - but was already frantically improvising with its manpower and machines. The baggage train hastily assembled in Regent's Park included one bright scarlet, commercial vehicle from a sauce manufacturer, which was handily visible to pilots from the air.

As British land forces hurried across France, civilians reported German troops in large numbers advancing through Brussels south-west towards Mons, 30 miles away. The RFC was tasked to confirm rumour by observation. At 10:16 am on 22 August, Lieutenant Bayly took off in Avro 504 No 390 flying as observer with pilot Second Lieutenant Vincent Waterfall - the rule that two pilots must not fly together had already been overridden by the need for qualified observers.

To the observer fell the duty of defence. At best, he would have carried a carbine, shotgun or Colt Browning revolver, or made do with a flare pistol; the first Lewis gun would not be mounted on an Avro until October. Tales abound of this new airborne fraternity saluting each other with courteous waves, before graduating to vigorous shaking of the fist, lobbing of bricks and then small arms fire. But, at this early stage of the war, armed only with a keen pair of eyes, Bayly's hands gripped his binoculars as firmly as they had a rugby ball at the put-in. Most missions were flown not for bombing or combat but for reconnaissance and artillery observation; aerial dogfights captured the public imagination but the reality of wartime aviation was far more pragmatic.

In August, however, the threat was not yet in the air but from the ground. Flying at 2,000 feet, Avro 390 flew over the Enghien-Soignies area at around 10.50, making a pass at just 20 metres or so, the Germans so surprised that they failed to fire a single shot at an easy target flying low and slow. The plane banked and returned towards one of the columns; the reception was ready this time. The Avro crashed by the roadside.

At a time when untrained anti-aircraft fire was more beginners' luck than judgment, the gunners must have been dumbfounded. The excited infantry of the 12th Grenadiers were quick to claim the kill. Their Captain, novelist Walter Bloem, wrote:

Suddenly a plane flew over us... I ordered the two groups to fire at it... the plane started a half-turn... but it was too late: it went into a dive, spun around several times then fell like a stone about a mile from here.

Bayly and Waterfall had no choice but to go down with their ship. Parachutes were not worn: the Air Board saw them as un-British, likely to undermine the crew's fighting spirit and desire to stay with their machine, 'which might otherwise be capable of returning to base for repair'. They died on impact in a mess of splintered wood and propeller blades. Little wreckage was left after burning fuel incinerated the doped canvas and ash frame. Unsure what to do with their first dead foe - the fallen fliers they called 'Black Angels'- the soldiers doffed their caps, fired in salute over the smoking wreckage and hastily covered them with four inches of soil. Local Belgians placed flowers for those who had flown to rescue them from invasion. The local landowner later exhumed the corpses and placed them in zinc coffins, hidden in his distillery cellar to await a decent burial. For the German commander, Von Kluck, the wrecked Avro and bodies in RFC flying tunics gave the first proof that British Expeditionary Forces were on the continent of Europe.

Bayly's reconnaissance report, unfinished and fatally interrupted, was found by Belgian peasants. His last words, scrawled at 11.00hrs, note: 'cavalry, 4 columns infantry, other group of horses and column turning left to Silly'. By the time this reached Command HQ it was of no practical use: the war had moved swiftly on, the retreat from Mons was in full flight.

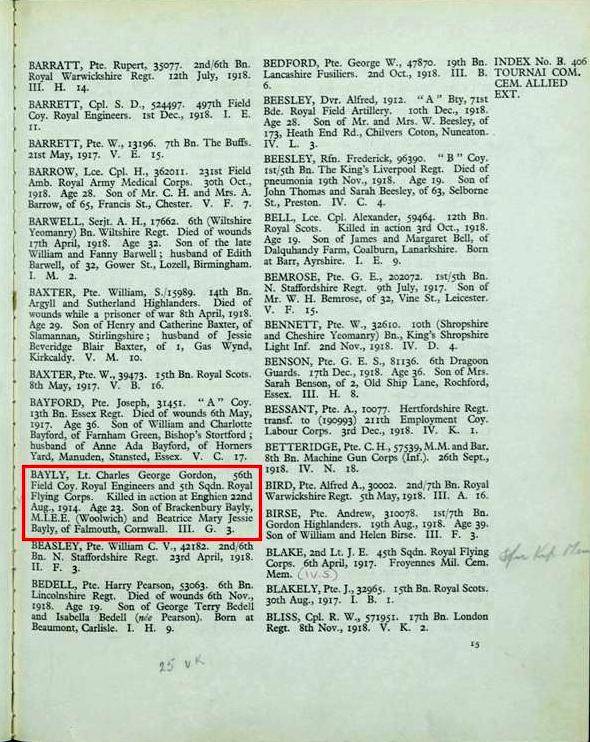

Bayly can claim the doubtful honour of flying in the first British aeroplane to be shot down by enemy fire - and more. Britain's 'other ranks' had already taken casualties: the first, Private Joseph Viles, knocked off his bicycle in Bristol on the very first day; sailors of HMS Amphion killed by a mine on 6 August. The first airmen, Lt Skene and AM Barlow, were killed in an accident as they took off from Netheravon on an inglorious Twelfth*. Private Bai, Gold Coast Regiment, died in Africa on 15 August. Three RFC men perished in crashes en route to Maubeuge. Private John Parr, another cyclist, was the first soldier to die by enemy fire on the Western Front. Bayly and Waterfall, therefore, were the first RFC (and so British Army) officers to die in action in the Great War, noted in de Ruvigny but largely overlooked since. Their Saturday morning flight to destruction narrowly preceded the death of Royal Scots Lieutenant George Thompson in Togoland. Bayly still lies in Belgian soil, his formal grave in Tournai Communal Cemetery since 1924.

Article and images extracted from The Final Whistle: the Great War in Fifteen Players by Stephen Cooper, published by Spellmount. and from the Western Front Association Web-site

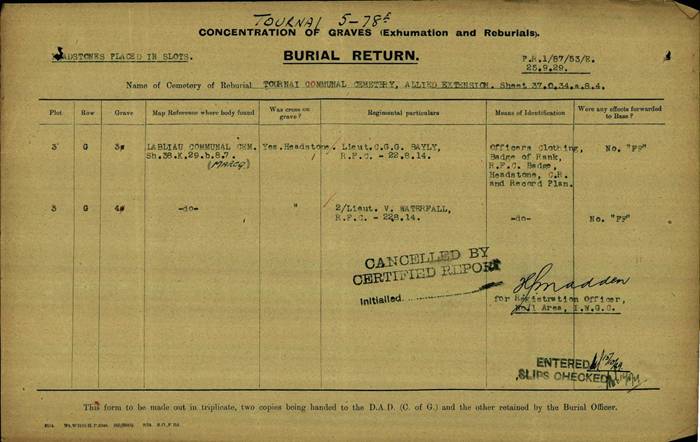

Certificat de scépulture

Certificat de scépulture